by Johanna Siegler // July 14, 2025

Few filmmakers working today so thoroughly unmoor the senses as Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. Since emerging from Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab—a crucible for reimagining the interface between anthropology and aesthetics—they have developed a body of work that resists the conventions of documentary form. Allowing themselves to be led by the camera, by the texture of environments or the resistance and unpredictability of bodies, machines and atmospheres, their method is guided by a deep commitment to embodied experience and the perceptual affordances of the tools they use.

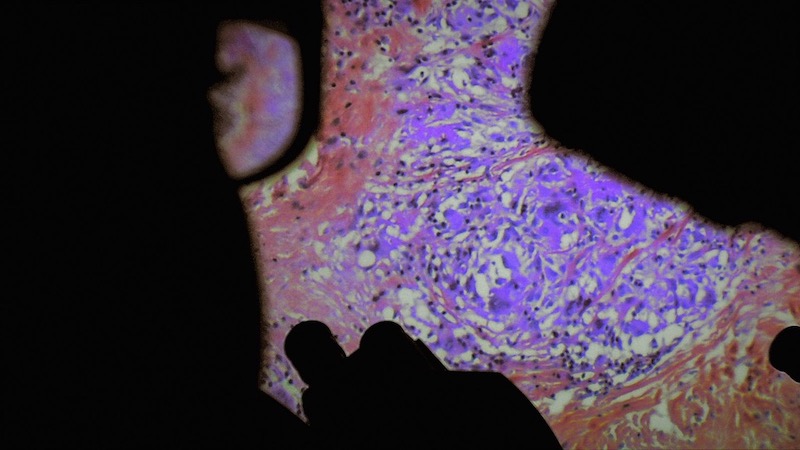

This openness to process is evident in their 2012 feature ‘Leviathan,’ which immerses viewers in the world of industrial fishing off the coast of New England. Using small, durable cameras affixed to fishermen, nets and vessels, the film foregoes narration and conventional framing in favor of a fractured, post-human sensorium, collapsing distinctions between worker and animal, and then at times, even sea and sky. In ‘somniloquies’ (2017), they drift through the unconscious via the recorded sleep-talk of Dion McGregor, while their latest film, ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’ (2022), enters the interior of the human body through surgical and endoscopic footage, rendering it a strange, microscopic and luminous terrain.

Across all these works, their cinema refuses to impose coherence on the world; it attends instead to its ambiguity, its strangeness and its irreducible materiality. This sensibility carries through into ‘Breathing Matters,’ the duo’s first comprehensive exhibition in Germany, on view at silent green in Berlin from July 17th. Installed within the architecture of the former crematorium, the exhibition gathers their major works in a spatial constellation. Alongside the installations, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel have curated an accompanying film and performance program, bringing together collaborators, peers and kindred practitioners. In our conversation, the filmmakers reflect on the intuitive, often opaque processes that guide their collaborations. They speak of a desire to remain open to encounters that reorder the sensible and, reflecting on ‘Breathing Matters,’ the rare experience of seeing their works cohabitate.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel: ‘Leviathan,’ 2012, film still // Courtesy of the artists

Johanna Siegler: I wanted to start with a question about a strong effect in your films. Perceptual estrangement. We see bodies or environments we think we know, but they become unfamiliar, even unrecognizable. What draws you to defamiliarization as a formal or perceptual strategy?

Lucien Castaing-Taylor: I don’t really remember us ever talking about being invested in perceptual estrangement. I don’t think we ever said, “This is what we want to do.” When we start a project, we don’t know where it’s going to end up. We just want some encounter with “the real” that is as unmediated as possible by conceptual or moral representational prejudice or a sense of déjà vu. I think we both feel that there are too many films in the world, just like there are too many commodities, too many artworks. Most of them don’t sell for a lot of money, but not many contribute to revealing reality to us in a way that we’re not able to anticipate. So we’re trying to do something new. A lot of other people say that our collaborations are characterized by an aesthetic and ethic of perceptual proximity or intimacy, that they’re super visceral. And we also don’t really talk about that, but it is, I think, obviously kind of true.

I remember seeing ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’ in Los Angeles, maybe a year after we’d finished it, in a kind of IMAX theater. I wasn’t going to watch it; I just had to be there to do a Q&A. But then, I got bored, so I went back and watched it, and I was like, “Jesus, this film is intense.” And if I wasn’t one of the filmmakers, I would kind of hate the film or hate the filmmakers. So I think our films are characterized by a kind of intimacy and proximity and sensorial overload—even though we don’t really feel it ourselves. But I don’t think we’re invested in estrangement.

The only way I would say that we are, is that we are invested in a kind of “aesthetic of unknowing,” or it not being obvious what we’re looking at, and not giving people, what in French you would say, too many “repères,” too many horizons. Not giving people their bearings totally. So you could say that’s a kind of estrangement, but it’s not different in kind from the forms of unknowing, or the kinds of uncertainty or the kinds of estrangements that characterize all of our daily lives. None of us go through life knowing much about the world. Most of our daily and nightly lives are spent in a sense of bemusement and questioning and uncertainty and doubt and despair.

Véréna Paravel: I agree. I realize it’s not something that we say to ourselves: “Oh, we want to defamiliarize the familiar.” But deep inside, this is what we are seeking. I think we are the first spectators of our own research. Even though we don’t know exactly what we are looking for, we always know that the moment we start to be interested in what we’re doing is when there’s something more opaque, more mysterious, that triggers more questions than closure.

When we are in front of something that reorders the relationship between beings or between things and beings—this redistribution of connection—maybe that is part of the estrangement that we are interested in. And it can take preconceptual ideas, but most of the time we come to that by trying and trying until we see an image that becomes something that is so mysterious, that it is a wonder. And that is always a starting point for us.

I think we usually have a simple way of connecting things together, of putting things into boxes, especially in the history of cinema, where you have the anthropocentric view. And I think the way we work, we are trying to reshape or reshuffle that. When Lucien said that he saw ‘De Humani’ in IMAX and he would hate the filmmakers, I think I had the exact opposite reaction. I recently saw it again and I don’t think I hated us. I was very curious about how we did it. It’s beautiful to watch a film you haven’t seen in a long time, when all the little intellectual thoughts you had during the shaping of it disappear. Suddenly you’re facing an object you don’t even recognize, and then questions start to come back again. That, for me, is a sign of being able to create an object that is endlessly opening new connections with time and space.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel: ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica,’ 2022 // Courtesy of the artists

JS: So maybe it’s more of a deconstruction of dominant ways of seeing, and at the same time, a sense of being implicated in everything that you film. This exhibition at silent green is in a different context—an art space. Your work has been shown in film festivals, museums and biennales. How has the shifting context changed the way you reflect on your work? Or how audiences engage with it?

VP: The last time we had an exhibition where most of our work was shown together, it was a very important moment. For the first time, I created associations between the works that I hadn’t before. Usually, we are so invested in each piece when we make it. Each one is a new universe. But suddenly, when all the work cohabits, the images and sounds bleed into each other. It’s like walking inside the unconscious of two beings who have worked together for years and years to the point of thinking alike. I saw, for instance, how our relationship to the body and the mind comes through. ‘Leviathan’ is very embodied, in the way we welcome different perspectives, a multi-species approach. Then in ‘Caniba,’ the body appears completely differently, but the face returns. Death is always there, interrogating the threshold between life and death. With ‘De Humani,’ we go a step further. Even when we are inside the body, it’s not isolating a body; it’s reconnecting it with the cosmos. I think we are going toward that direction.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel: ‘Caniba,’ 2017, film still // Courtesy of the artists

JS: How involved were you in the curatorial process at silent green?

LCT: Well, we didn’t build the crematorium, obviously. So we’re constrained by the architecture and by what silent green has made of it. But we did plan it together, subject to the constraints of the space. Constraints can also be enabling. The ramp where the hearses would descend is where we’re installing ‘The Last Judgment,’ and that works incredibly well—it’s amazingly fortuitous. That film is the most serene, the least visceral, and yet perhaps the most apocalyptic. Spatializing ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’ on seven or eight screens in the main space is a really interesting use of the space. Others are more sequestered, but there’s a kind of elliptical, proto-narrative to how one moves through the show. It works well. We discussed it with the whole team, and until we went in person—we may still change everything in the week before the opening—but overall, I think it holds together.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel: ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica,’ 2022, film still // Courtesy of the artists

JS: The exhibition is also accompanied by a program of works and artists you invited. Did that curatorial act shift how you see your own work—through contrast or resonance?

VP: Yes. I realized recently that it’s maybe the most joyful part of showing a work. It’s like harvesting, calling back all the people who are engaged in making art or thinking, a kind of tribe of people who are inspiring to us. Rather than always showing the same work, with the ego looking at itself, being in dialogue with others is a way of rereading it, keeping it alive.

Recently, I invited a singer and musician to Jeu de Paume. After showing ‘somniloquies,’ we took dreams from Dion McGregor, the dreamer in the film, and I wrote some text. He put it to music. We did a concert. The dreams took on another dimension that doesn’t exist in the film or alone. It was a gift—to the public, to Dion, to myself. These programs are important. Also to highlight other people’s work, people who are politically engaged, who care about sound and image, who share the same kind of exigency with the real. We invited a friend, an anthropologist, who made a very important film about Palestine. She comes from the Sensory Ethnography Lab, too. Ernst Karel, who worked on all our films, is coming. It’s a way of being more collegial. I don’t love the word “community,” but yes, maybe an artistic cluster of people still trying, still maybe believing that art can do something. Especially now.

Exhibition Info

silent green Kulturquartier

‘Breathing Matter(s) – Véréna Paravel & Lucien Castaing-Taylor’

Opening Reception: Thursday, July 17; 7pm

Exhibition: July 18-Aug. 24, 2025

silent-green.net

Gerichtstraße 35, 13347 Berlin, click here for map